|

Eager Space | Videos by Alpha | Videos by Date | All Video Text | Support | Community | About |

|---|

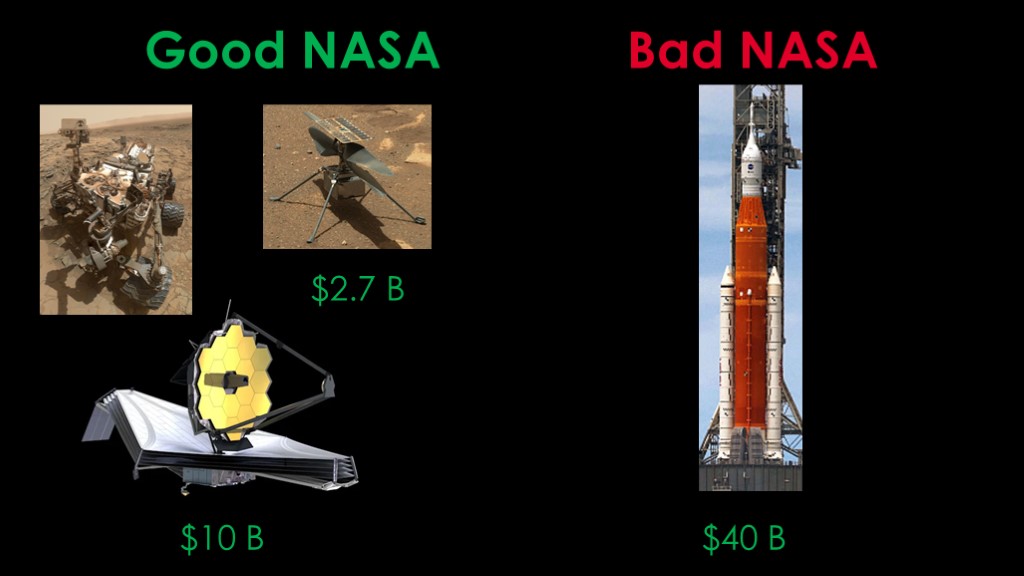

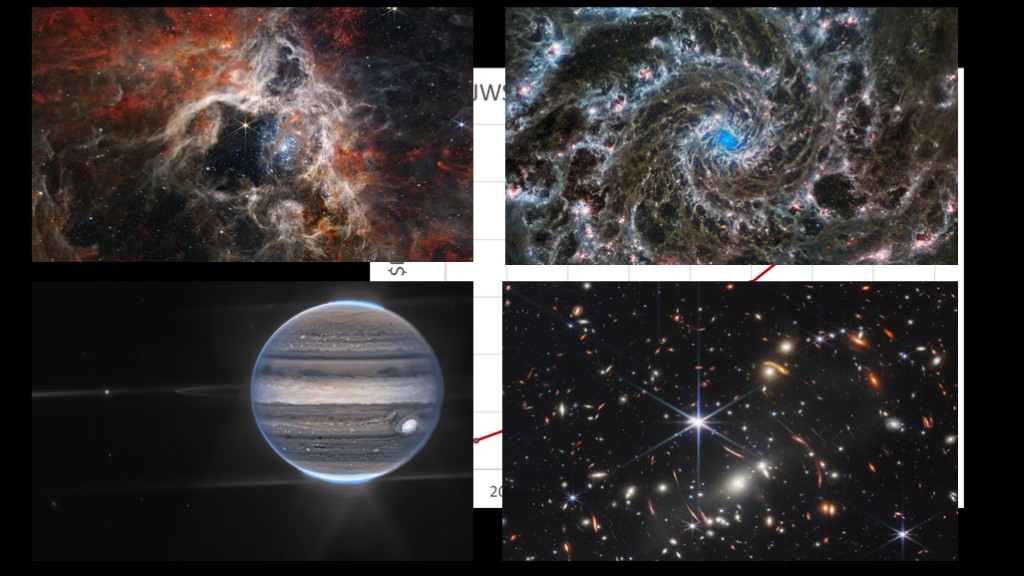

In the past 5 years we've seen NASA do some amazing things.

They've sent the very capable perseverance rover to Mars, and included the first aerial vehicle to fly on Mars, the ingenuity helicopter.

They finished the long-delayed James Web Space Telescope and successfully deployed it to a challenging location.

Perseverance and ingenuity will cost about $2.7 billion total, and James web is about a $10 billion program. Large amounts of money, but with very meaningful results.

SLS and Orion are inching their way towards their first uncrewed flight around the moon, and so far their cost is something over $40 billion. When operational, they are scheduled to fly up to 1 mission per year.

How can an organization that is so great at science be so terrible at creating a new launch system?

That is the subject of this video

NASA is a large organization, and we're going to start by looking at large organizations and how they operate.

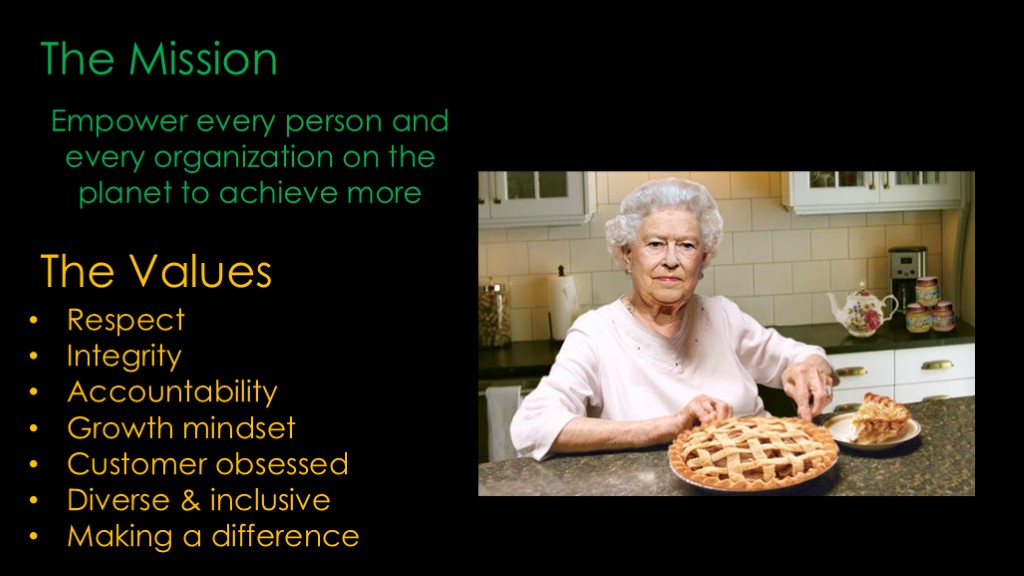

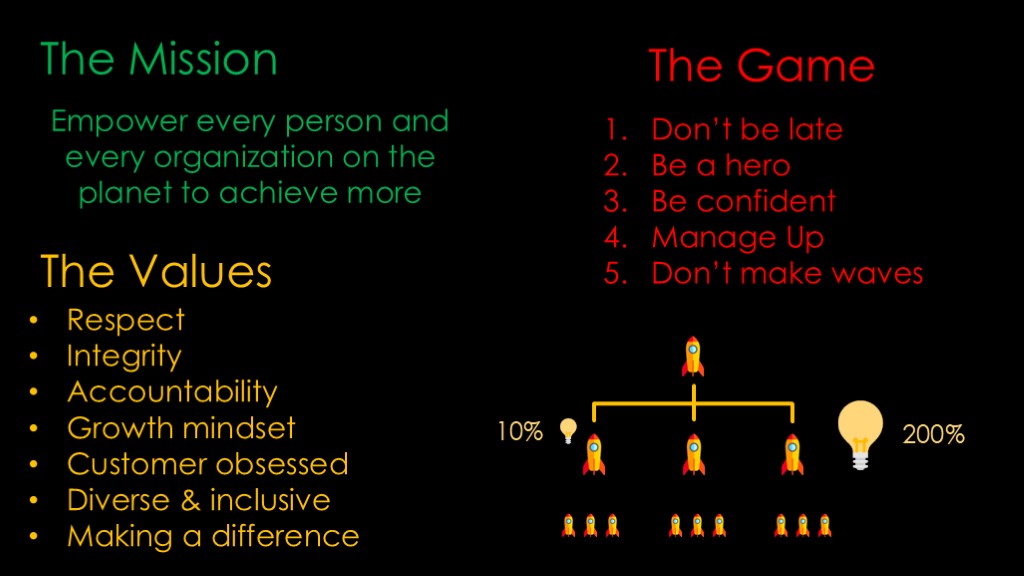

We'll start with the mission of the organization, which is something like this:

Empower every person and every organization on the planet to achieve more

These are typically high, flowery statements. I bet that almost nobody can tell me which organization has this particular mission statement.

Next are the corporate values, which are respect, integrity, and accountability. And that's it.

There's nothing wrong with either the mission or the values, but they are largely motherhood and apple pie - who will stand up to say that empowerment, respect, integrity, and accountability are a bad thing?

Let me add in a few cultural values - growth mindset, customer obsessed, diverse & inclusive, and making a difference. Any guesses?

The company is, in fact, Microsoft. I did leave out the "one Microsoft" value as it was a bit of a giveaway.

This is a public statement of what Microsoft values, how they want to be seen by the world. How does that map to the inside of the company?

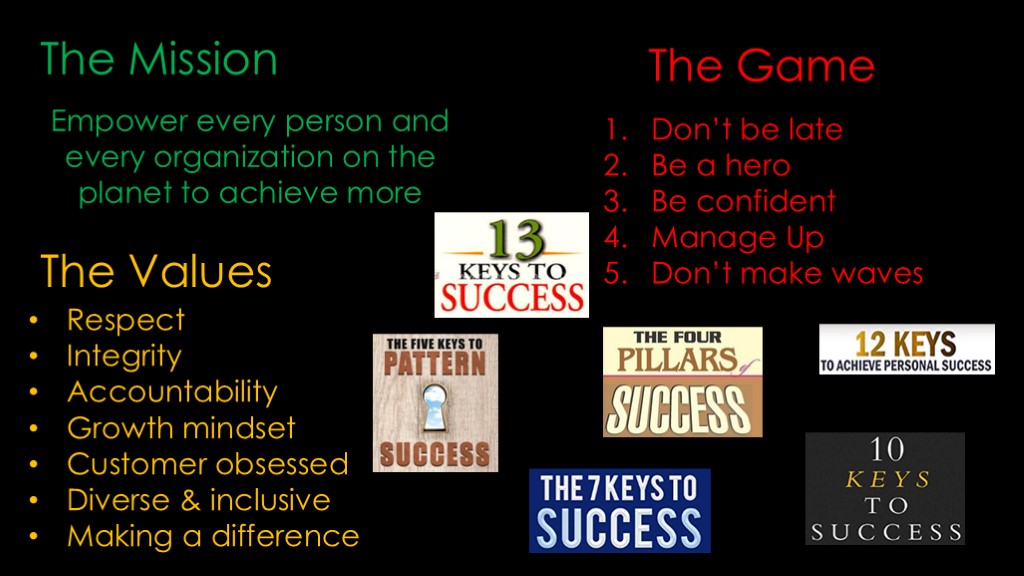

What goes on inside any organization is what I've taken to calling "the game". And I'm picking on Microsoft here, but I can confidently tell you that every large organization has their own version of the game.

The goal of the game is simple - it is to move up the ladder in the company, to get more money, more reports, more power, more budget, more respect. The game is about *career*, and very much about career for "the people who matter" - management, and especially executive management.

The rules to the game are a secret - they aren't written down anywhere and they not only differ from one organization to another, they differ in different parts of an organization. You are unlikely to find them in any of the books you read about success.

Here is one set of rules of the game:

Rule 1: Don't be late. It's not good for you or your management if you are the one who is visibly slowing things down. Submit your software even if it's buggy because everybody else is doing the same thing and you won't get attention for buggy code. If you are late, don't speak up; everybody is playing schedule chicken and you just need to be sure you aren't the latest one.

Rule 2: Be a hero. You *will* get kudos for extra effort to stay on schedule even if it's your poor skills that put the schedule at risk.

Rule 3: Be confident.

Rule 4: Manage up. To be promoted, you need the support of your manager, your manager's peers, and your second-level manager. They need to know your name and be comfortable that you are the kind of person they would be comfortable working with.

Rule 5: Don't make waves. The game is predictable when everybody is following the rules and that makes it easier for everybody.

Let's look at a little example of how the game works.

Here's part of an organization, with three first level lead managers and a second-level manager they report two. The reports are small because they are generally not participants in the game, which they would typically refer to as "politics".

Let's suppose the first lead implements an idea that results in a 10% improvement in productivity. That's good for the lead; they are helping the company and it's good for the manager as it shows that their reports are doing a good job.

Now let's suppose the third lead implements an idea that results in a 200% improvement in productivity. That sounds great.

This idea makes the other two leads look bad, and if given the choice between implementing the same idea or making the third lead look bad, they will choose the easier choice. The third lead has not made friends with his peers.

The third lead has also caused problems for his manager. If anybody finds out about this improvement, they will expect the manager to implement it across all three leads, and the increased performance in the manager's group will not make the manager's peers or manager happy.

Finally, the third lead had three reports to do the work they were doing, but they are now 200% more productive and only need one. But one report is too few, so the lead can't be a lead any more.

That's what happens if your idea is very successful. If you try something and it isn't successful - or it isn't obviously successful - be assured that your peers will not forget about it going forward.

There is generally one high-level value that the game rewards the most, and that is conformance. Follow the rules and stay within the norms of your peers, and you'll do great.

You do need to know what the mission is but in most cases you aren't evaluated in your contribution to the mission, because it's simply not feasible to do so.

The values are useful inside the game; you can refer to them in a positive way to move people ahead, and in a negative way to hold people back. "I like Joe but I don't think he has enough of a growth mindset to take on larger challenges".

That's the way the game is often played in large organizations with professional management. But it's not the only way it is played...

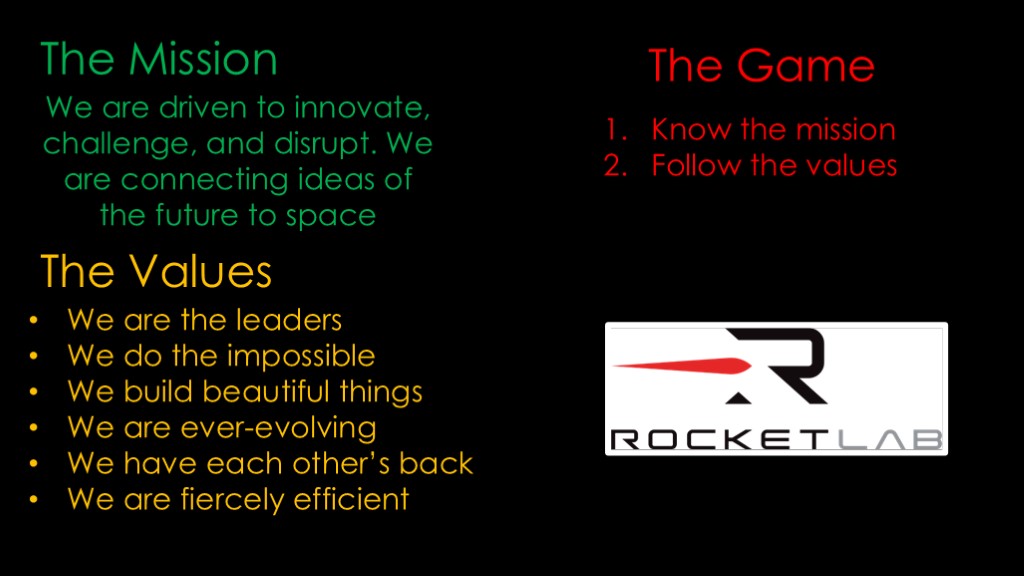

Let's say you are a small launch company still run by a founder. You likely have a very different kind of mission and values.

Note that the missions and values are very specific and are *not* motherhood and apple pie. You can actually use them to decide how you should act as an employee and you can use them for employee evaluations.

The game in this company is likely very simple - know the mission and follow the values.

And this can work because a) the founder is in control and not willing to employ anybody who is trying to play a different game and b) the only path to success in the game goes through mission and values because otherwise the company fails.

It's this sort of alignment between the mission, the values, and the game that can make small startups so nimble.

If you were wondering, the mission and values here are from Rocket Lab. That's true even if you weren't wondering...

Another way of stating what we just went over is the following

Read:

The incentives are what drive the game.

Thankfully, we can finally move to NASA.

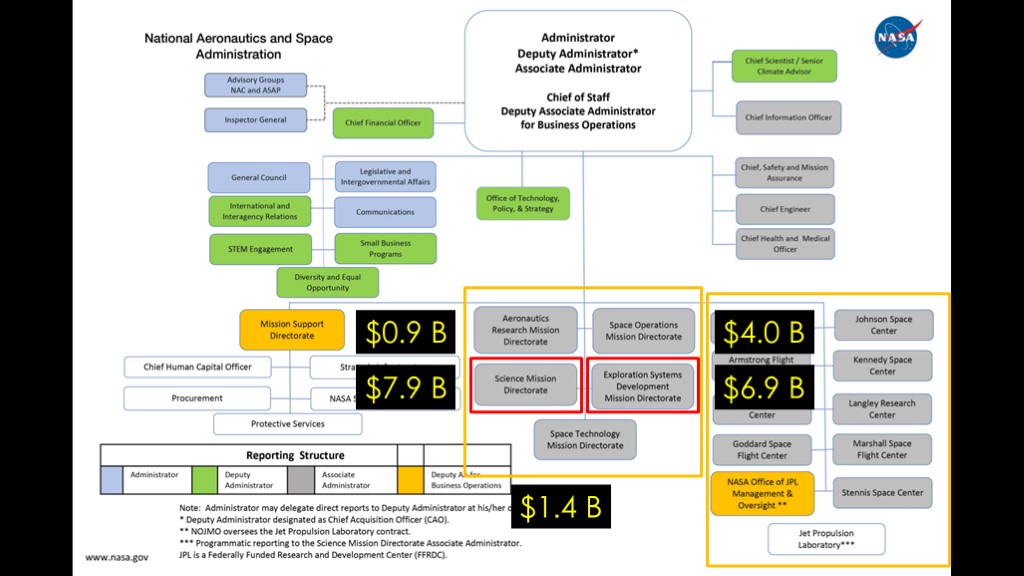

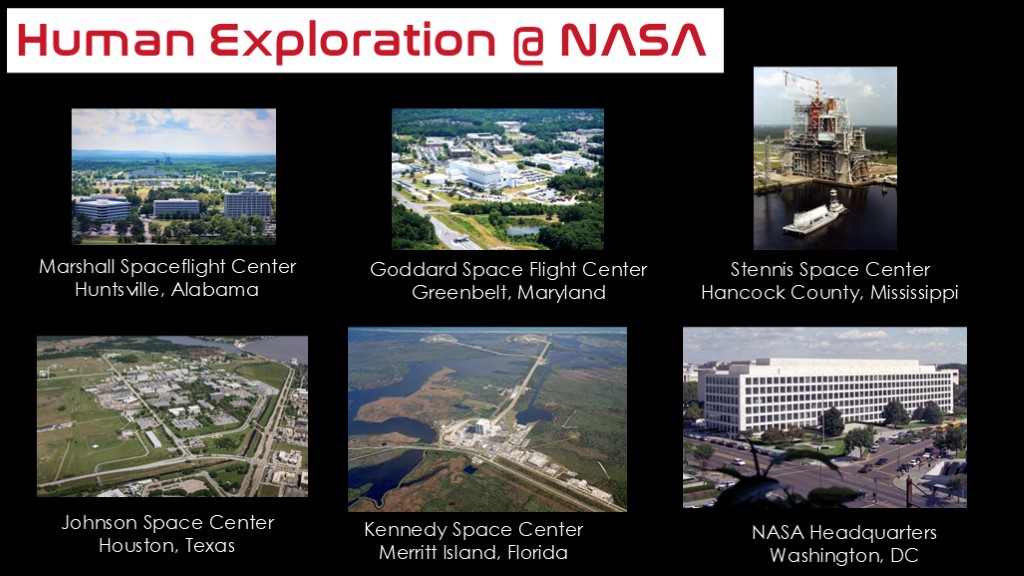

NASA is a big and complex organization. The two notable parts are the Mission directorates and the various centers. Roughly, mission directorates define work and centers perform work.

We'll focus on the 5 mission directorates.

The first is aeronautics research, which spends a little less than a billion per year

The second is space operations, which includes running the international space station and crew flights to and from the station. It spends about $4 billion each year.

Science is about $8 billion.

Exploration systems development includes everything Artemis - SLS, Orion, gateway, and the human landing system. It's about $7 billion.

And finally, there's Space Technology, which covers - not surprisingly - development of new technology for future NASA missions. Things like advanced thrusters, nuclear thermal engines, nuclear reactors for space power, etc. It's about a billion and a half.

We're going to focus on the science and exploration systems development directorates because they show the best and worst of NASA.

How does science at NASA work?

Science starts with figuring out we know and what is interesting to research.

At NASA, science is guided by a series of decadal - ten year - surveys created by the national academies of science. The commissions for each area of study pull together the top researchers in the field to decide what is known in a specific area, what questions are interesting, and how to answer those questions. This information is summarized in the decadal survey documents, each running several hundred pages in length. The NASA ones are:

Planetary science, earth, solar, biological and physical, and astronomy

In some cases these are about doing things in space, in some cases they aren't - the astronomy one covers both space-based observatories and ground based observatories.

The actual research happens outside of NASA, in a large number of independent projects - some small, some medium, and a few large.

To figure out what research NASA should fund, NASA maintains a series of science directorates that align with the decadal surveys. These directorates are responsible for looking at the goals in the decadal surveys, looking at the research proposals that have been made in that area, and choosing the ones that best accomplish those goals.

This sort of model is not unique to NASA; it's pretty much how all government funded science is handled.

Let's look at a few examples.

List separate parts.

Decadal surveys

Competitive proposal program

Psyche & book that talks about it.

List of ongoing programs.

Notable failures, some that turned into successes (hubble, JWST).

NASA science succeeds through a competitive grant environment and farming out the majority of the actual work to academia, including the operation of JPL, which is a federal research laboratory.

They do what they need to do - to organize and choose what is important - and leave the rest to academia. And they do a large number of programs.

Look at history of their biggest programs?

The recent DART mission was built by the applied physics laboratory at Johns Hopkins university.

It also flew the lee-cheeya cube satellite, built by argotec for the Italian space agency.

The currently postponed psyche mission spacecraft was built for Arizona state university by maxar technologies, and the instruments are created and operated by johns Hopkins applied physics laboratory, UCLA, MIT, and JPL.

If you want to know more about what it takes to put a planetary mission together, I highly recommend the book "A Portrait of the Scientist as a Young Woman" in which Lindy Elkins-Tanton describes her experience as a researcher, including being the primary investigator - or group leader - for psyche.

Another good example is the Perseverance Rover. The rover was created by the jet propulsion laboratory, but the 7 instruments that ride on it were chosen from 60 proposals and come from research institutions around the world.

You've noticed that I put up two different JPL logos, one with NASA and one without.

JPL is a federally funded research laboratory that is run by the California institute of technology, so it's more like a research arm of a university. Funding for JPL comes through NASA but NASA does not run JPL in the way it runs the NASA centers, though JPL and NASA do work very closely together.

NASA has had some issues on the science side.

In 1990 the hubble telescope was launched, with optics of unprecedented quality. Unfortunately, in an attempt to save money, NASA had chosen a bid that did not subject the telescope to full-scale testing on the ground, and an error in a mirror testing device resulting in a mirror that was perfectly made to the wrong specifications and therefore yielded poor results.

Three years later NASA installed a set of corrective lenses - and other upgrades - as part of a NASA servicing mission using the space shuttle, which fixed the problem.

The James Web Space Telescope program was started in 1998, and at that time the plan was that it would launch in 2007 at a cost of $1 billion.

As the years went by, the project slipped and got more expensive, finally launching 15 years late and at nearly 10 times the original budget. That increase in cost meant that it took $9 billion away from other research projects.

But these concerns have largely gone away due to the early success of JWST, not only in terms of science but in producing such phenomenal images.

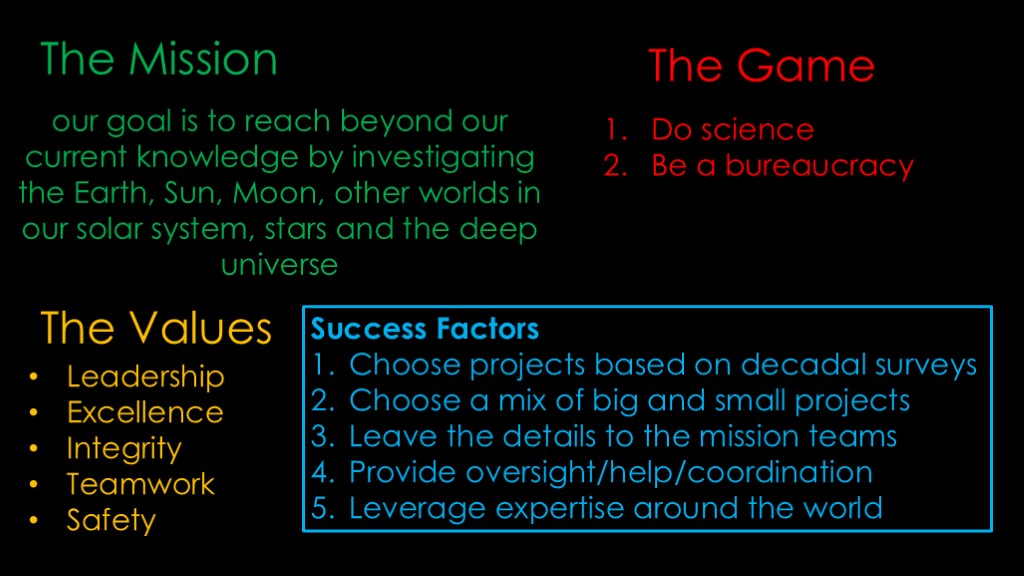

Here's the mission and values for the NASA science directorate. Their game is mostly just "do science" - the things that make you successful in science will likely make you successful here. It is a government bureaucracy, but that's what big federally-funded science is, and being a bureaucracy has not been a significant obstacle.

They have a number of success factors.

First, they choose projects based on the decadal surveys, which is the best scientific opinion about how to use limited funds.

Second, they choose a mix of big and small missions.

Third, they leave the details to the mission teams - NASA provides the grant money and the teams go off and execute using those funds.

Fourth, they provide oversight, help, and coordination for those mission teams, both in figuring out how to create their proposal, who to work with, and how to work well.

Fifth, they leverage expertise around the world.

The NASA science directorate has had some issues, but they are generally science done well.

We'll now switch from the science side to the human spaceflight and exploration side.

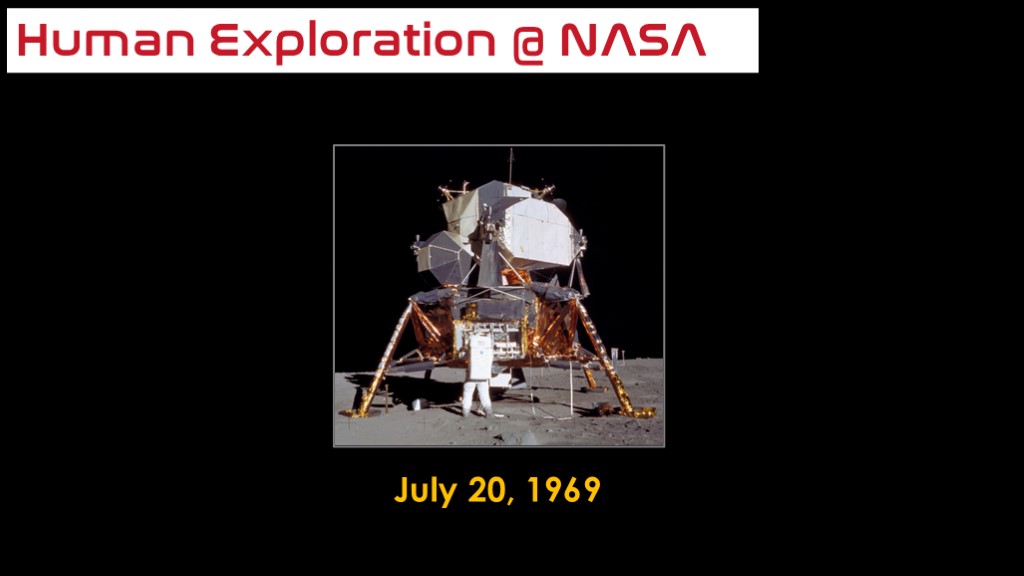

During Apollo, things were very simple.

The mission was beat the Russians

The values were beat the Russians

And the game was beat the Russians.

This unity of purpose is one of the main reasons Apollo was successful; it was a *national* goal, and while all the contractors were happy to get Apollo money, nobody wanted to be the one who kept the country from winning the race.

On July 20th, 1969, Neal Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first humans to land on the moon, and the US won the race to the moon.

This was a wonderful day for NASA and all the contractors that worked on Apollo.

It was also a terrible day.

The whole point of Apollo was to achieve what Apollo 11 achieved - to land humans on the moon and return them to earth. The mission was accomplished, the race was done.

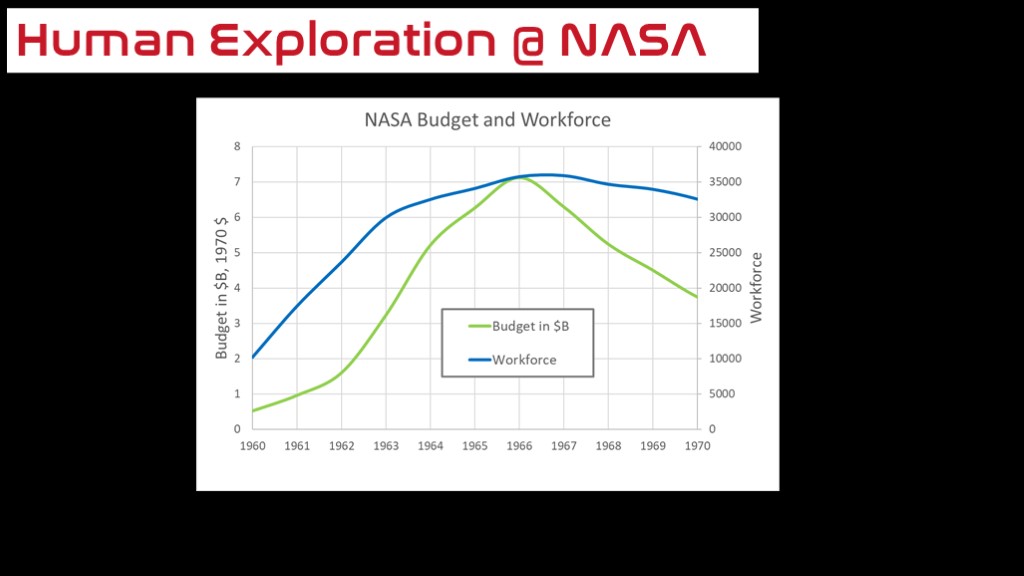

NASA's budget had already been going down since the peak in 1966 and by 1970 it would be half the peak. NASA had already made painful cuts in their workforce, and with the race won, it was possible that congress would eliminate all human spaceflight funding.

That would be bad for all the NASA centers that worked on Apollo, and bad for the managers employed at NASA Headquarters in Washington, DC.

And bad for the major contractors that worked on apollo and their numerous subcontractors

And bad for the congresspeople with NASA centers or major contractors in the areas they represented.

The situation defined the game; it was:

Keep NASA spaceflight centers open

Keep money flowing to NASA contractors

Keep votes flowing to congresspeople

Preserve NASA management jobs

The mission was literally "whatever we can sell to keep the game going"...

And the values - I'm sure there were values, but against an existential threat to NASA's existence, there wasn't much time for values.

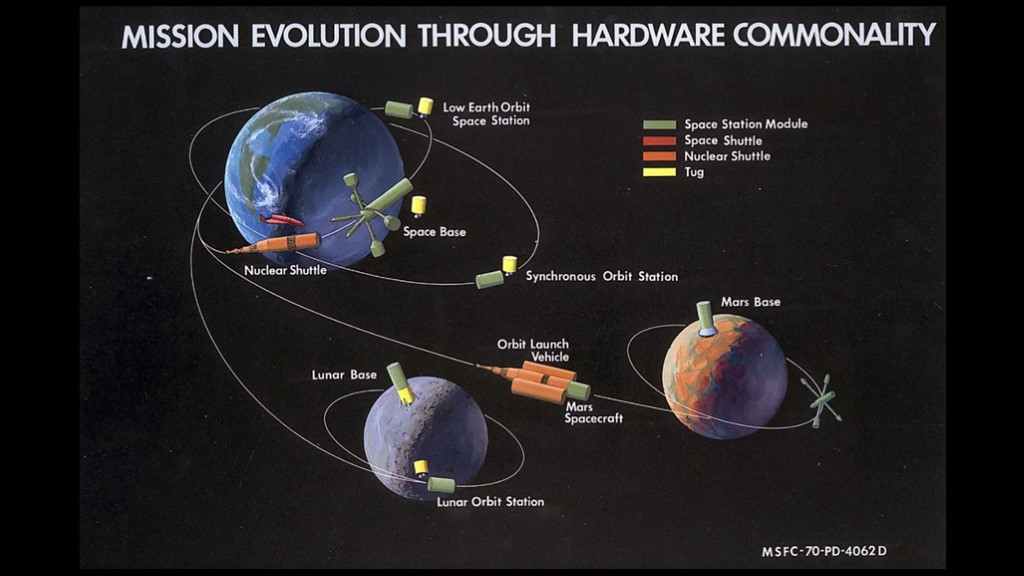

NASA had some ideas for the post Apollo era - space stations, nuclear tugs, moon bases, and even Mars bases - but they would be very expensive and none of them was politically possible as both congress and president Nixon were uninterested in further exploration.

There was another option:

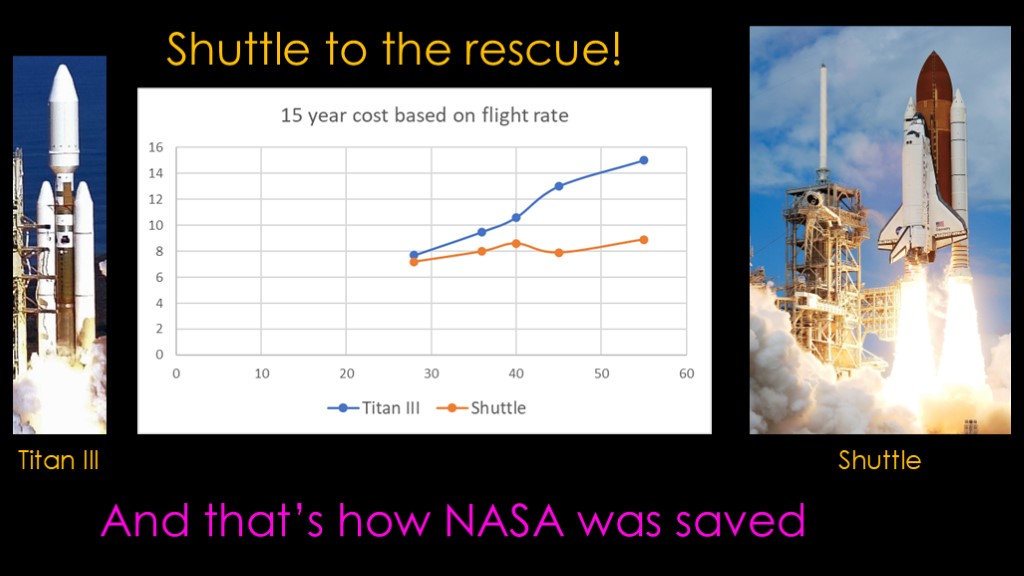

The current government and DoD launcher was the Titan III, which was $20-30 million per launch. That's about $150-230 million in 2022 dollars, so roughly what an Atlas V would cost.

The government wanted a cheaper launcher than the Titan III, and that provided an opportunity for NASA.

NASA believed they could build a "space shuttle" for $5 billion and it would cost $5 million per flight.

With a bit of math, you can come up with this chart, and it shows that if you fly 28 times per year for 15 years, you will save money with the shuttle approach. NASA projected that they could fly up to 60 missions per year, at which point it would be much cheaper than Titan III.

NASA horse traded with the Air Force to get DoD support for the shuttle, and based on that support and this economic argument, the shuttle program was approved and NASA was saved.

The mission became "Build and Fly Shuttle".

You've probably noted that "fly the same vehicle to the same place over and over" really isn't an exploration goal, but remember that it's the game the matters.

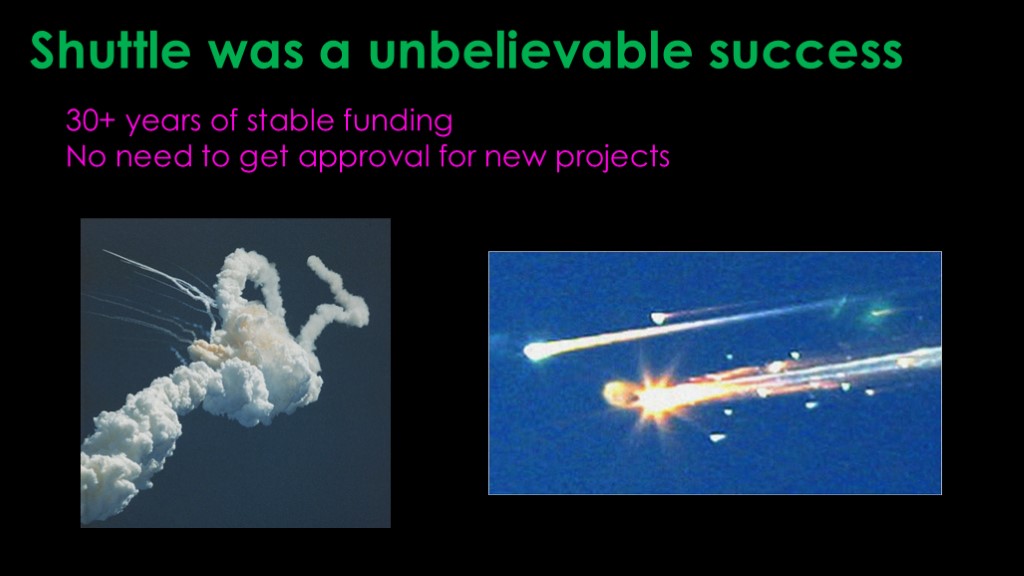

Shuttle was an unbelievable success; it put NASA in a stable funding environment for 30 years and there was no need to go back to congress to justify a new program. Money for NASA, money for contractors, votes for congresspeople. Stable careers all around. For those that matter, it was great, and that is why NASA flew it for so long.

It's true that it was very expensive, it killed 14 astronauts and destroyed two $ billion orbiters, and it never went beyond low earth orbit, but none of those factors are important to those that matter.

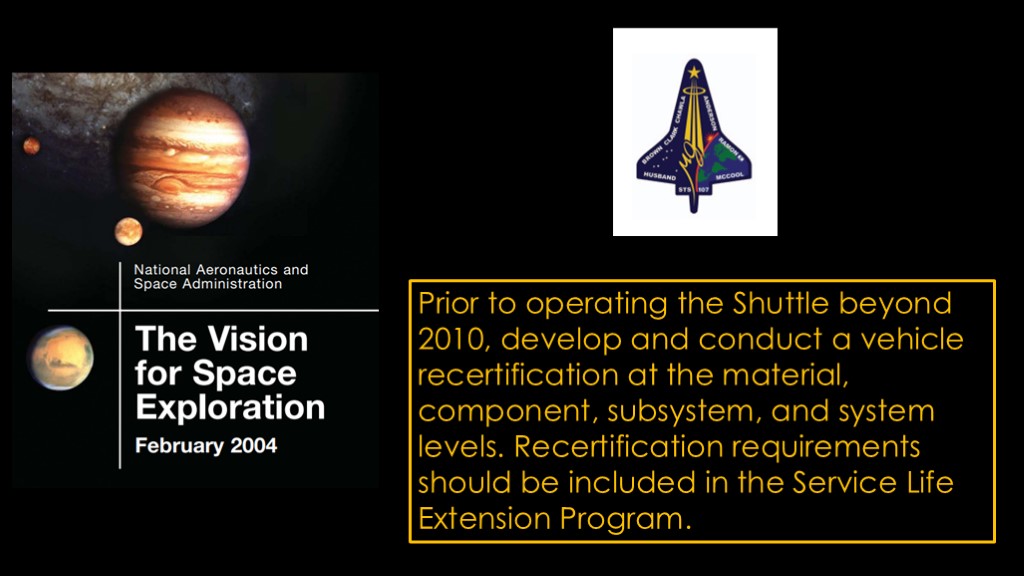

It is widely believed that the Columbia disaster was what led to the cancellation of the shuttle program, but that's not really true. The investigators did not recommend cancellation; they merely recommended a recertification process similar to the ones that are common for military aircraft. NASA had plans to operate shuttle to 2020 or even beyond.

But in 2004, the Bush White house released a new "Vision for Space Exploration".

The mission in the previous years had been merely "fly shuttle" and "build ISS".

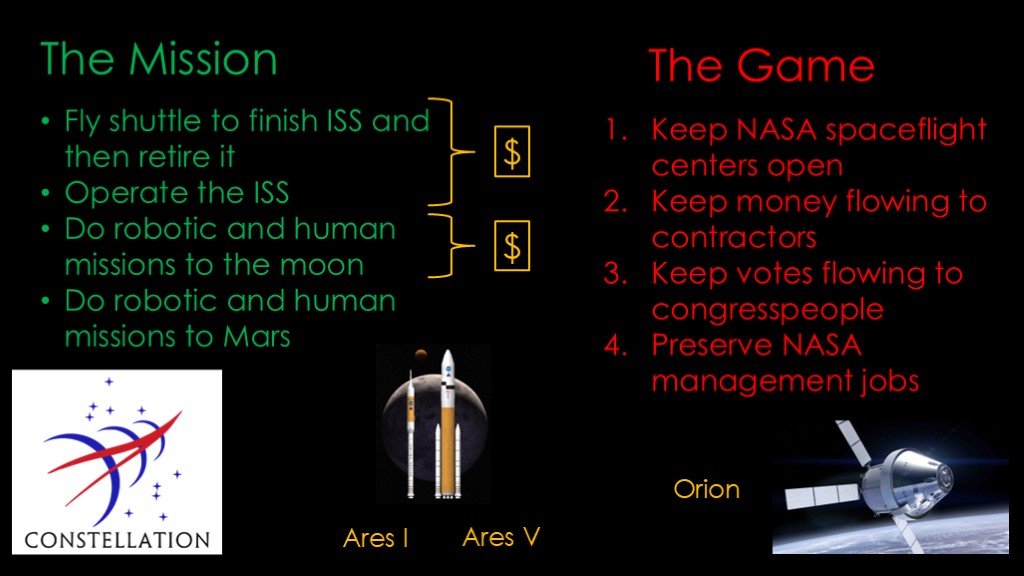

There was now a new mission. The first two items are similar - fly shuttle to finish ISS and then retire it, and then operate the ISS.

And then there are things that look like real missions - robotic missions to the moon followed by human ones, and then the same thing for Mars.

It would be really great for NASA to do something beyond low earth orbit with a defined mission, but there's a big problem.

These first two items were already consuming 100% of NASA's exploration budget. The plan was to continue them until ISS was done - probably 5 years - while at the same time start up a program with a similar scope to Apollo. It's pretty obvious that there was a budget issue here; there was no way NASA could afford working on the things they said they would be working on.

But remember that it's the game that matters, and there was certainly a lot of opportunity here for everybody involved, so NASA started down this road with the constellation program, including the Ares I crew launcher, the Ares V cargo launcher, and a new deep space capsule known as Orion. The two Ares rockets were shuttle-derived because that is what the rules of the game required.

In 2010, there was a fight between the Obama administration - who wanted to cancel Constellation because of the budget issues - and congress, who wanted to keep the game going.

Not surprisingly, congress won, and the mission was the big orange rocket, Orion, and maybe Mars at some sufficiently distant point in the future.

The sole bright spot was the commercial crew program.

And then finally, in 2017 we got a rebranding of the previous program into "Artemis", and shift towards the moon instead of maybe mars at some point.

And that's the state where we currently are. The Game is still mostly driving the NASA exploration programs, though the success of commercial crew and the award of the lunar lander to SpaceX has changed things a bit.

The main problem is with the exploration systems development mission directorate.

If we look at their mission description, it's all about system development. This is why, until 2017, there was no real mission for SLS or Orion; the goal of the directorate is simply to develop them.

What we need is an independent decadal survey for *exploration* and a NASA mission directorate in charge of implementing that survey.

But, of course, that hasn't happened, because it would interfere with the game.

Is it possible to change the rules of the game? I believe the answer is yes, but that's a topic for another video.

If you enjoyed this video, please join my kickstarter for the NASA exploration game.